“No one would create without monetary incentives.”

Surprisingly, many opponents of copyright firmly believe that the above statement accurately reflects the views of creators and the creative industries—that they think but for copyright, creativity would not exist.

It provides an easy target to knock down: “Clearly, people have created for thousands of years before copyright existed.” The conclusion seems to be that if copyright is not necessary, then it isn’t justified.

Law professor Eric E. Johnson is currently writing a series of posts on “the great fallacy of intellectual property“. He describes this fallacy this way: “The long understood theory for why IP rights are necessary has been that people won’t invent useful technologies or create worthwhile art and literature without having the right to profit from their labors.”

We can call this the “fallacy of intellectual property” fallacy.

It’s a fallacy because it doesn’t accurately state the theory behind copyright. The economic justification for copyright is that it is an incentive to create—not a necessary condition. True, there exists a base level of drive to create knowledge and culture. But, as knowledge and culture are fundamentally important to a democratic society, an incentive to create above and beyond this base level provides significant benefits to that society.

In addition, the “fallacy of intellectual property” fallacy fails to account for an arguably more important function of copyright. Copyright provides an incentive to invest in creation.

“In a private market economy, individuals will not invest in invention or creation unless the expected return from doing so exceeds the cost of doing so — that is, unless they can reasonably expect to make a profit from the endeavor.”1Mark Lemley, The Economics of Improvement in Intellectual Property Law, 75 Texas Law Review 989 (1996). Creative works require financial investment. Some, like movies, require more than others, but all works require some level of investment. The inherent risks of investing in creative works makes copyright protection more important. Creative works also require investment in time—not only the time spent creating, but the time a creator spends honing her skills.

How Piracy Harms Investment

First, let’s talk about how online piracy has harmed investment in creative works. I’m focusing mostly on creative intermediaries—book publishers, record labels, film studios, etc. Individuals certainly invest in their own works, but the bulk of investment comes from intermediaries.

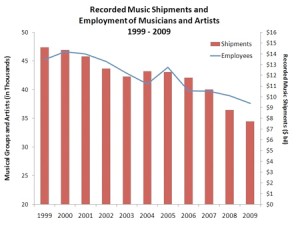

Insufficient enforcement of online piracy has led to a reduction in investment of creating new works. The following chart shows how employment in the music industry and new releases both fell at the same time online piracy has grown.

Additional evidence shows how weak copyright protection reduces investment in new works — harming new and local artists particularly. According to the IFPI’s Digital Music Report 2010:

- “In Spain, which has one of the highest rates of illegal file-sharing in Europe, sales by local artists in the top 50 have fallen by an estimated 65% between 2004 and 2009;

- France, where a quarter of the internet population downloads illegally, has seen local artist album releases fall by 60% between 2003 and 2009;

- In Brazil, full priced major label local album releases from the five largest music companies in 2008 were down 80% from their 2005 level.”

Leveraging Investment

Intermediaries provide much-needed resources and expertise for producing high-quality works. But they perform another function that is just as important: aggregating the risk of producing creative works.

Economists sometimes refer to creative works as “experience goods“. The value of a book, movie, or song is difficult to judge beforehand, unlike other consumer goods. Consumers cannot determine if a particular work will be satisfactory until after they experience it.

Experience goods are thus risky to produce. How risky?

History suggests the risk is quite high. Remarks from several participants in the 1876 Royal Commission on Copyright in the UK cast light on the situation over 130 years ago. One William Smith said that “only one book in four” recoups its expenses, with one Anthony Trollope following up that he had heard from two separate publishers that “not one book in nine has paid its expenses.”2Minutes of the Evidence Taken Before the Royal Commission on Copyright.

These percentages hold true today. In the music industry, only about one in ten record albums sell enough copies to break even on expenses.3“Most RIAA members report that less than 10% of their releases are profitable”, David Baskerville, Music Business Handbook and Career Guide, pg. 339 (Sage, 2006); “A 1980 Cambridge study showed … approximately 84 percent of record albums failed to sell the allotted amount in order to break even”, Patrice L. Johnson, Are Black Entertainers More Likely to Receive Unfair Contract Agreements Than Their White Counterparts? Independent study, 1998. Film is similar—perhaps even worse. One economist has calculated that less than 3% of independent films produced break even.

Yet, creative industries can thrive under these conditions with appropriate copyright protections. And those intermediaries that do build sustainable businesses continue to invest in the next generation of creative works.

According to the IFPI, record labels reinvest around 30% of revenues into developing and marketing artists—$5 billion a year globally:

Recording contracts typically commit artists and labels to work together to produce a series of albums. Artists benefit from heavy upfront investment that would be difficult to secure elsewhere and record labels have the opportunity to recoup their outlay over a period of time.

Achieving commercial hits is the basis of the “circle of investment”, by which music companies plough back the revenues generated by successful campaigns to develop new talent and help fund the next generation of artists.

Continually investing in new talent is a hugely risky business, as only a minority of the artists developed by music companies will be commercially successful in a highly competitive market. Estimates on the commercial success ratio of artists vary between one in five and one in ten.

By aggregating risks, intermediaries—record labels, book publishers, film studios—can leverage their profits on hits toward the creation of a wider variety of new works. The 10 or 20 per cent of projects that break even help fund the creation of the 80 to 90 per cent of projects which don’t. This benefits niche works, works without mainstream appeal, and new creators who have not yet gained an audience.

Cultivating Genius

The expenses of creation include not just money but time too. Writing a book—especially fiction—doesn’t involve much of a financial burden. But it does take a good deal of time—time that is in short supply for many.

More importantly, time is needed for developing creative skills. While people may have some level of natural talent, few if any are born fully-realized artists. Pop economist Malcolm Gladwell famously said it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill.4Check out Ericsson, Roring & Nandagopal, Giftedness and Evidence for Reproducibly Superior Performance: An Account Based on the Expert Performance Framework, 18 High Ability Studies 3 (2007), for some of the research behind Gladwell’s claim.

In Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith writes:

And thus the certainty of being able to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men’s labour as he may have occasion for, encourages every man to apply himself to a particular occupation, and to cultivate and bring to perfection whatever talent or genius he may possess for that particular species of business.

Copyright provides that certainty that encourages the investment of time to cultivating creative talents.

The alternative—relying only on innate motivation to drive development of creative talents—is not as attractive to a society that values creativity and culture. British historian Thomas Babington Macaulay recognized this as long back as 1841.

You cannot depend for literary instruction and amusement on the leisure of men occupied in the pursuits of active life. Such men may occasionally produce compositions of great merit. But you must not look to such men for works which require deep meditation and long research. Works of that kind you can expect only from persons who make literature the business of their lives. Of these persons few will be found among the rich and the noble. The rich and the noble are not impelled to intellectual exertion by necessity. They may be impelled to intellectual exertion by the desire of distinguishing themselves, or by the desire of benefiting the community. But it is generally within these walls that they seek to signalise themselves and to serve their fellow-creatures. Both their ambition and their public spirit, in a country like this, naturally take a political turn. It is then on men whose profession is literature, and whose private means are not ample, that you must rely for a supply of valuable books.

And this idea continues to be recognized today:

It has been said that people would create entertainment without being paid to do so, and I have no doubt some would. But everyone has to buy groceries and pay the rent. So the universe of those who would create for free would be limited to amateurs and the independently wealthy. Unless we’d be satisfied with their meager output, we need some way to provide financial incentives that permit people to create entertainment professionally, for a living.5Lionel Sobel, Why the Digital Piracy War has to be Fought, November, 2002, DGA Magazine.

Again, notice no one is saying that without copyright, no one would invest in developing their talents in creative fields. What’s being said is that because of the “public goods” nature of expressive works, the amount of people able to make that investment is limited without copyright.

The copyright incentive increases the ability of creators to invest time in perfecting their skills, allowing a wider range of voices to be heard and a higher quality of works created.

Journeyman Hierarchy

Now consider all the ancillary skills that go into producing creative works: the skills of book editors, recording engineers, film crews. Copyright industries in the US employ millions of people beyond what we would consider “primary” creators. Yet their skills, and their mastery of those skills, are just as vital to creating high-quality works.

The idea that innate motivations to create are sufficient to ensure an optimal level of high-quality creative works fails to take into account these ancillary roles. They require even more of an incentive to invest in their development.

A system that protects the rights of creators also supports the ability of those outside the limelight to perfect and master their skills.

In an interview with Chris Castle at Music Technology Policy, Songwriters Guild of America president Rick Carnes calls this a “journeyman hierarchy”, and talks about how it results in higher quality works. He uses the example of Spike Lee, who began with a student film. Based on that success, he was able to get funding for his next film and begin a career as a filmmaker. Along the way, actors such as Denzel Washington got their start and behind-the-scenes workers developed their skills. This continual cycle is what creates the “next generation of art.”

Carnes notes that great films and great music delve into ideas that inspire and challenge. Professionals create these types of works better than anyone else because it’s their job; they do it day in and day out, giving up a great deal of their lives to do so. But if copyright is not properly enforced, than people cannot get a return on their investment; if people cannot get a return on their investment, they’re less likely to invest in the next generation of art.

Bad Literature Drives Out Good

Creators have a variety of incentives to create besides those provided by copyright. The “fallacy of intellectual property” assumes that, in the absence of copyright, these other incentives would ensure a sufficient supply of high caliber works of knowledge and culture. This assumption, however, is doubtful.

“Without copyright protection,” write William Landes and Richard Posner, “there would be increased incentives to create faddish, ephemeral, and otherwise transitory works because the gains from being first in the market for such works would be likely to exceed the losses from absence of copyright protection.”6An Economic Analysis of Copyright Law, 18 Journal of Legal Studies 325, 332 (1989). Think more “Reality TV”, less Mad Men. More remakes and sequels, less original works.

History shows this principle in action. In Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates, Adrian Johns describes the experience in France during the French Revolution:

Briefly, after 1789 the revolutionaries wanted to see enlightenment spread from Paris by its own natural force. They therefore abolished literary property … What ensued was an experiment in whether print without literary property would help or hinder enlightenment … This was a revolutionary utopianism of the commons … But as utopias do, it turned rotten. The craft of printing did expand rapidly—the number of printers quadrupled—but what it produced changed radically too. The folio and the quarto were dead. Reprints became legitimate, then dominant … [Printers] employed whatever secondhand tools they could lay their hands on, worked at breakneck speed with whatever journeymen they could get, and ensured a rapid turnover by issuing newspapers and tracts with an immediate sale. What books were still published were largely compilations of old, prerevolutionary material. In other words, a literary counterpart to Gresham’s Law took hold, and the triumph of the presses grises led to disaster.7Pg. 53, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Investment of time and money in creators and their works leads to a wider variety and higher quality of expression that enriches all our lives. Copyright, when it is properly enforced, provides an incentive to make that investment.

References

| ↑1 | Mark Lemley, The Economics of Improvement in Intellectual Property Law, 75 Texas Law Review 989 (1996). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Minutes of the Evidence Taken Before the Royal Commission on Copyright. |

| ↑3 | “Most RIAA members report that less than 10% of their releases are profitable”, David Baskerville, Music Business Handbook and Career Guide, pg. 339 (Sage, 2006); “A 1980 Cambridge study showed … approximately 84 percent of record albums failed to sell the allotted amount in order to break even”, Patrice L. Johnson, Are Black Entertainers More Likely to Receive Unfair Contract Agreements Than Their White Counterparts? Independent study, 1998. |

| ↑4 | Check out Ericsson, Roring & Nandagopal, Giftedness and Evidence for Reproducibly Superior Performance: An Account Based on the Expert Performance Framework, 18 High Ability Studies 3 (2007), for some of the research behind Gladwell’s claim. |

| ↑5 | Lionel Sobel, Why the Digital Piracy War has to be Fought, November, 2002, DGA Magazine. |

| ↑6 | An Economic Analysis of Copyright Law, 18 Journal of Legal Studies 325, 332 (1989). |

| ↑7 | Pg. 53, University of Chicago Press, 2009. |

Pingback: Tweets that mention The “Fallacy of Intellectual Property†Fallacy | Copyhype -- Topsy.com

In a democracy the law must reflect the will of the people. The increased transience of information has changed this will so people are less inclined to honour the legal protection in place. Ergo, the copyright laws currently in place, legislated in most countries from a time before even CDs could be copied, are an anachronism, as is any business model which fails to account for the internet.

Legislative reform is required to ensure the law is not undermined.

Actually, in this democracy, the law must reflect the will of the people if the will of the people doesn’t violate the Constitution. What the commenter is describing is actually mob rule, not constiutional democracy. While there appears to be a demonstrable yearning for mob rule and pirate utopias amongst the digital natives, it’s not here yet. Copyright is a Constitutional right, but as we have seen in other bodies of law, a Constitutional right without a remedy is no right at all.

Not only is copyright a Constitutional right, but international human rights treaties protect the rights of artists (separate from intellectual property) as human rights. It is axiomatic that human rights are protected from mob rule. That’s the point.

It is the Internet that must accommodate the rule of law, not the other way around–if we are to continue living in our democracy.

I agree that piracy is a big problem, but what seems to get missed is the legal art of “Music Streaming”. I hardly see how creators will make a living from the Micro-payment system of music streaming that now seems to dominate how music is delivered.

From this I predict we will all loose… As explained above, if there is no ability for creators to get a return on their investment, like any other business, it will fail and close shop… This in turn, again explained above will leave in its wake a see of mediority for those who listen… Soon listeners will get tired of crappy music and find other entertainment to occupy their time…

Those content providers who give away music virtually for free would then be unable to profit from their venture as well.

The idea of FREE will not sustain itself… But unfortunatly, that won’t stop anyone for gorging themselves till they finally bust…. What then??? We start over… Maybe I’ll be lucky enough to still be around for that……

I would like to point out that there are quite a few assumptions that I feel are simply wrong : in the art production process money is not an incentive (I am talking about art production – not mainstream entertainment). I find it hard to explain why … but most good literature has been written by people not having any financial benefits from doing what they have been doing. I am German – so I will add some examples : Gottfried Benn is the literature superstar of Germany post war literature. He says in his auto-biographie that he makes 3,5 DM a poem – a misery even by post war standards. He had no incentive. Arno Schmidt is another example he is sponsored by some rich Germans – but never actually makes money with his books when living.

Now people like Stephen King make money – but that just good entertainment – nothing I would call literature or art production (don’t get me wrong – I like Stephen Kings book and I have never read Arno Schmidt biggest book – but they just don’t play in the same league).

Jean Luc Godard thinks copyright is a bad concept for the movie industry altogether. He argues that the huge Hollywood budgets destroy films – make it impossible to make movies. I think he as a point – a lot of big budget production look like well made commercials (and in a way they are). I ve seen recently some real good movies in Czech Republic made by some FEMU students on a 1000USD budget. Money does not drive quality … maybe for cars – not for art production.

Copyright might be a valid concept for the industry (and that includes the entertainment industry) – but it does not make any difference on art production.

sorry just throwing in one more idea – there has been a lot of people in particular in fields like science and IT that do have access to more knowledge because the internet allows easy sharing of knowledge – including what is commonly called “piracy”. My personal guess is that if knowledge would not have been shared that radically over the last decades we would be a good 10 years behind todays technology.

Criticizing Stephen King as “just good entertainment” is not just condescending, it demonstrates a complete lack of understanding regarding the intensely practiced skills required to produce the superlative quality of literature that Mr. King outputs.

Does anybody think that writers like Stephen R. Donaldson, Neal Stephenson, Ayn Rand, and others could take the time to create their intense masterpieces if they had to do it for free?

Having worked in the art world, I can state emphatically that the majority of the best artists create to make their living. Without copyright and the ability to protect themselves from piracy of their intellectual property, there would be far less superlative art for the rest of us to enjoy and be inspired by.

Thank you, Terry, for a cogent, well thought and written article.

Come on,let’s face it! Theft is theft whether one robs a bank, steals an idea, or copies and sells a work of literature, music, or art. The creator of a work of art has nothing else to sell but his product. If a man works in a factory, building an automobile, and his boss assigns that man’s work hours to his own brother-in-law’s paycheck, that is not freedom, nor magnanimity, nor right. It is amazing how so many people who who not want to be gypped of their paycheck hours feel so free to rob an artist.

What really frosts me is the concept that everyone “gets it” when we speak of “investment.” This definition of “investment” is always based upon financial investment. Everyone seems to agree that the financial ‘investor” has a right not to be cheated. No one acknowledges the artist’s investment — of time, lessons, practicing, planning, creating, writing, and recording. What hypocrisy!

Merely because composers and artists of old were all ripped off does not mean that it is OK to continue ripping them off. Get real! Be honest!

You trust the IFPI numbers?

I would truly look at something such as BBC discussing the upward trend than the trend going downwards by a chart that is all sorts of inaccurate. First, what does it represent? Only RIAA artists? Only CD sales? Why are we looking at only their sales when there’s so much more of the pie that is on the table? Namely, we don’t know anything about independent artists sales, RIAA and indie combined concert sales, or any other data that tells of the welfare of the industry.

“In a private market economy, individuals will not invest in invention or creation unless the expected return from doing so exceeds the cost of doing so — that is, unless they can reasonably expect to make a profit from the endeavor.â€

I’m beginning to wonder if you’re quoting people out of context… I’ll have to read Mark’s views into improvement along with the further rationale of Prof. Johnson who seems to understand that perhaps copyright law needs to be changed in some circumstances.

“Spain”

I did a little research and Spain has been doing quite well with Spotify. Along with the rest of Europe, where in the US, we can’t get that service because of our copyright laws.

France

Hadopi has been in effect for six months now? It has had a great effect on the economy there…

Brazil

If I remember correctly, music is made for other purposes. The same rhythms occur, but people are more into dancing and remixing as quickly as possible, greatly influencing the culture of Brazil. It’s accurate that the IFPI complains about this competitive streak in people to put their music out as soon as possible. What isn’t accurate is how someone can condemn competition, which greatly influences other areas. Ex. Artists don’t make much money on the CDs themselves, but if you look at the artists, dancers are encouraged to take classes along with large boom boxes being bought for vans, stimulating the economy.

” In the music industry, only about one in ten record albums sell enough copies to break even on expenses.”

RIAA Accounting is to blame for expenses. The artists are forced to make money elsewhere. That was where touring came in. But with artists able to make their own success, the labels can’t rely on the old methods of success. If anything, they truly hurt themselves by screwing over the artists.

“Copyright provides that certainty that encourages the investment of time to cultivating creative talents.

The alternative — relying only on innate motivation to drive development of creative talents — is not as attractive to a society that values creativity and culture.”

I seem to be coming to a different conclusion to Macaulay’s words. Namely thus:

“You cannot depend for literary instruction and amusement on the leisure of men occupied in the pursuits of active life. Such men may occasionally produce compositions of great merit. But you must not look to such men for works which require deep meditation and long research.”

If you’re taking too long in life, you can’t depend on certain men to constantly put out books of worth.

” Works of that kind you can expect only from persons who make literature the business of their lives. Of these persons few will be found among the rich and the noble. The rich and the noble are not impelled to intellectual exertion by necessity.”

Paraphrase – you get lazy when you’re at or near the top. Funny how he says this exact thing and it’s mainly the RIAA/MPAA that complain about piracy…

” They may be impelled to intellectual exertion by the desire of distinguishing themselves, or by the desire of benefiting the community. But it is generally within these walls that they seek to signalise themselves and to serve their fellow-creatures. Both their ambition and their public spirit, in a country like this, naturally take a political turn.”

The motivations of the affluent will be to distinguish themselves or “benefit the community” (I would think this is a time period where perhaps the rich looked down upon people?). However, their motivations are driven by the politics of the time.

” It is then on men whose profession is literature, and whose private means are not ample, that you must rely for a supply of valuable books.”

Usually, the ones who aren’t rich, who are eager for their own desires, will supply valuable books.

“What’s being said is that because of the “public goods†nature of expressive works, the amount of people able to make that investment is limited without copyright.”

I find that a false statement… There are so many avenues to being published are writing as an amateur, becoming a professional, that you really can not say that copyright is needed. I have heard of books being written when they were put on Scribd for full view to everyone.

Youtube has new music everyday. Blogs can be written for free. There have been a number of artists that once were amateur that have gotten a professional start by proving to financiers they are a commodity. I can only take that with a grain of salt since there’s less evidence of investment being limited without copyright.

“Think more “Reality TVâ€, less Mad Men. More remakes and sequels, less original works.”

That already happens in the form of soap operas, celebrity gossip magazines, and Twitter. I would suggest looking into the Pareto Principle. The bad stuff falls while the good stuff rises. Just like copyright might be hitting an early death since it seems to be more and more dated as time goes by.

Pingback: Music Biz News: Apple Launches Mac App Store, We7 Hits Ireland, Nielson Stats, HMV Shutters & More - hypebot

@ Lee Fox

If a personal opinion is that Stephen King is “just good entertainment” then it’s just that. An opinion. It’s not mired in fact that Stephen King deserves to ruin the lives of 20 people because they looked at the pdf of “IT” free on the internet before they went to buy the book. Everyone seems to ignore the possibilities that the internet has awakened. Music artists have a great deal of options with technology to be heard. And yet, copyright, as it’s used now, is done to prevent people from sharing. For example, Ted Williams is having his interview shared right now! The problem is you have to go somewhere else on Youtube to get it.

I wonder… What does the art world look like? Did you try your hand at the digital world? Have you done things to constantly master your style? How did you differentiate yourself?

@PatrickF

*sigh* If I share a digital work of someone’s with others on the internet (like on a Reddit site) I doubt highly it’s the same as going into someone’s home and taking a copy of the Mona Lisa. It’s almost the same as someone going into a museum at the same time with others to admire a work. Music has grown greatly with newer offerings that aren’t happening in the US because of overreaction. The flawed need to shut down filesharing has stymied our growth as people are now using music, games, and literature in new unseen ways. For music, I refer to Spotify. Why is it not available in the US? Ask the recording labels. The labels in Europe are making a KILLING from the freemium model, and yet the labels in the US don’t want it here without large upfront costs. For games, I’ll refer to Crimson Echoes here. They had a great story, a great concept, which no one acknowledges because of Square’s determination to take it down. While they complied you have to consider this… The game is 10+ years old. They updated the story and worked on it for 3 years alone. When they contacted Square, they received nothing in the form of a reply except a nasty DMCA letter later on. It’s as if the only people allowed to work on a game that has had no updates is Square itself. Now put that attitude into other fields. If Marie Curie was the only person to work on radiation, would we be where we are today in MRI technology?

No one is ripping off an artist. But you can’t gain a dollar that no one is spending. If you want people to support you, then you have to work with the tools involved.

Youtube

Livestream

Last.fm

Myspace

Deviantart

Livemocha

Quite frankly, if your music/game/work is not being shared at all, you have far more problems than copyright. I just think it’s fairly valid to see that copyright is a crutch more than an assistance tool. It doesn’t incentivize others to create and works to stifle competition more than anything else. With all of the options above, can artists find an audience? Can they find ways of success? How does it make sense to stop the progress of artists as technology removes barriers?

I’ll skip the moral debates, if I may, as we have been hearing them since 1997 at the Midem in Cannes and they don’t make a blind bit of difference.

One area where the effect of large-scale “sharing” is evident is in movie financing. Of all the risky investments, movies must be up there somewhere. Traditionally, producers have relied on advances from VHS and the DVD sales as part of their financing. The simple fact of downloading in lieu of renting a DVD on a large scale is killing that form of retail – and therefore the ability to invest in future productions.

And whereas in the music world, the offhand advice has been, “Oh go on tour, mate”. That can’t be done with movies and the sheer scale of upfront investment makes it impossible anyway.

This won’t kill the movie industry. But just like music, we’ll have a super-strata of Hollywood fare, no middle ground and then a snake pit of micro-budget productions.

Is that what we want?

” The simple fact of downloading in lieu of renting a DVD on a large scale is killing that form of retail – and therefore the ability to invest in future productions.”

But isn’t Netflix successful with streaming after a long time with DVDs? Not to mention demand for Hard drives, servers, and places for streaming movies means money to be made in other areas, correct?

So… If people are making movies and giving them out for free… Isn’t it safe to say, they can make money in other avenues as well?

It’s like saying you want silent, black and white movies, when technicolor and the Wizard of Oz is the newest thing.

“… we’ll have a super-strata of Hollywood fare, no middle ground and then a snake pit of micro-budget productions.

Is that what we want?”

There’s bound to be middle grounds… Short films to prove the talent of new directors and producers, or films made just for fun. The alternative is the IP fallacy that you’ll stop the ocean of torrents, downloads, movie watching and music consumption by taking down legal sites through faulty means and suing people for ungodly amounts of money.

Nice post. Your points are particularly strong when thinking about movies and television – these are enterprises that require much capital and organization of labor, and absent enforceable and predictable property rights, capital will not be deployed. It’s similarly true in music and books, of course, but it is harder for people to understand how important and capital-intensive promotion and curation is. Without it, a book is just a bunch of bits lost in too much content.

A couple of points.

Is this really a prominent perspective among copyright scholars? You cite to one professor holding this view, but I’m doubtful of your suggestion that “many opponents” hold the views you ascribe to them (I’m assuming here that you mean prominent or scholarly opponents, rather than random people on the Internet). I studied copyright under one of the professors who most agitates for a re-imagining of the copyright system, and even he didn’t seem to propose anything like this.

Perhaps I’m just hanging around the wrong parties, but most of the objections to copyright that I’ve encountered (among those who know the law) relate to the unjustifiably long duration of copyright under US law right now, and the argument that the system as a whole insufficiently benefits creators (and instead benefits industry). I’m willing to be corrected on the prevalence of this view, but as it stands now this looks like an attack on a straw man.

Correlation is not causation. Moreover, it’s not even clear how much correlation there is here — the IFPI report notably provides no matching data regarding piracy rates over this same time frame. There’s no doubt that some of this loss resulted from piracy, but how much? Are some of the losses better explained by the availability of substitute products (such as online listening services like Pandora, or substitute forms of entertainment such as video games)? Did piracy really get so much worse in the 2006-09 time frame, when the graph shows the most dramatic decline?

The data you provide are insufficient to support this assertion. Some digging around (cites for your graph would have been helpful here) shows that the number of new shipments is based on Soundscan data. But how much of that decline is due to decreased “investment of creating new works,” and how much is due to artists choosing to pursue modern alternative avenues of distribution? (I’ll also note that you provide no data for the amount of investment in the creation of new works.) Finally, how much change can be explained by the effects new technologies have on distribution and creation techniques? Computers, the Internet, and modern online marketplaces help lower the costs of creation and distribution, and reduce the need for specialists to perform these roles; how does that play in?

Note that I’m not arguing that piracy has no negative effect on these quantities. Rather, I’m taking issue with your attempt to make an empirical argument in support of your claims, when even the GAO notes that it’s incredibly difficult to draw any conclusions from the data we currently have.