Two hearings today will look at the current state of the US Copyright Office—one in front of the House Judiciary Committee on the Office’s functions and resources, and a budget hearing by the House Appropriations Legislative Branch Subcommittee looking at the Architect of the Capitol and the Library of Congress (The Copyright Office is a department within the Library of Congress). Besides the registration of copyrights and recordation of copyright transfers and assignments—and be sure to check out the Office’s report on Technical Upgrades to Registration and Recordation released earlier this month—the Copyright Office is more broadly responsible for copyright policy and education. However, it is currently underfunded, understaffed, and faces structural and technological impediments to its mission. The witnesses at the Judiciary Committee hearing will discuss the challenges under the status quo in more detail and offer suggestions for improvement, ranging from increasing the resources and autonomy of the Office to establishing the Copyright Office as an independent agency.

The Copyright Office has evolved tremendously since it was first created 118 years ago, and I think it’s commendable that its role and status, along with its functions and resources, are being fully examined.

Centralizing Copyright

When the delegates of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 drafted the plan for a federal government, they forewent a legislature with general, indefinite powers, such as the States enjoyed, for one that had authority only according to an enumerated list of under 20 powers. One of these powers was securing the property rights of authors at the federal level because, as James Madison would explain in the Federalist Papers, “the States cannot separately make effectual provisions for†this protection. 1Federalist 43.

For nearly a century afterward, Congress played a relatively hands-off role in copyright policy. It occasionally held hearings and amended the copyright laws, but otherwise remained passive. Copyright law did require registration, but this function was administered by federal district courts.

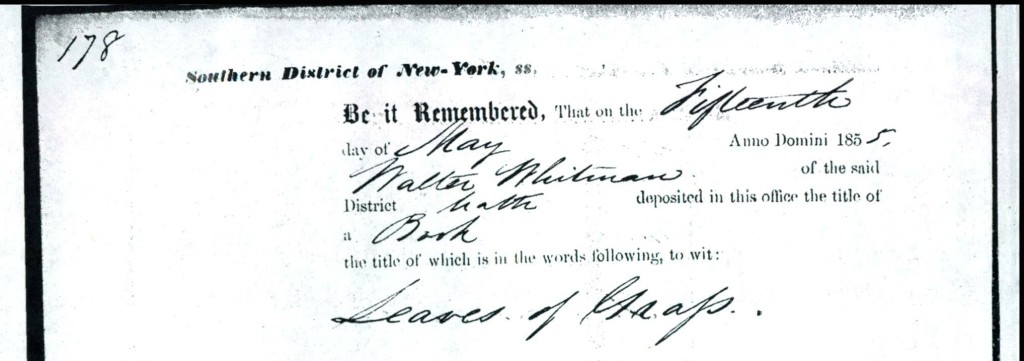

Copyright registration certificate for Walt Whitman, “Leaves of Grass”, 1855.

That began to change in 1870, when Congress centralized copyright registration and deposit functions within the Library of Congress. 2Act of July 8, 1870, §§85-111, 41st Cong., 2d Sess., 16 Stat. 198, 212-16. Then Librarian Ainsworth Spofford was a staunch advocate of using copyright deposit as a means of building the Library’s collections; he lobbied heavily for bringing copyright functions entirely within the Library’s purview, saying,

Under the present system, although this National Library is entitled by law to a copy of every work for which a copyright is taken out, it does not receive, in point of fact, more than four-fifths of such publications.

The transfer of the Copyright business proposed would concentrate and simplify the business, and this is a cardinal point…. Let the whole business… be placed in the charge of one single responsible officer, and an infinitude of expense, trouble, and insecurity would be saved to the proprietors of Copyrights and to the legal profession. 3John Y. Cole, Of Copyright, Men & a National Library, The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Vol. 28, April 1971. See also A Visit to the Library of Congress.

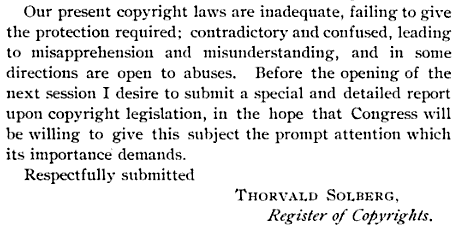

But Spofford underestimated the amount of work that would go into administering copyright registrations. Before the end of the century, Congress created (through an appropriations bill) a Copyright Office as a separate agency within the Library, headed by a Register of Copyrights. 4Act of February 19, 1897, 54th Cong., 2d Sess., 29 Stat. 545.

The Copyright Office Grows

The Copyright Office’s importance quickly grew. The first Register, Thorvald Solberg, proved ambitious, and established the Office as a legislative and policy expert, writing recommendations and drafting legislative proposals that would eventually become the Copyright Act of 1909. 5Abe Goldman, The History of USA Copyright Law Revision from 1901 to 1954, Copyright Law Revision Study No. 1, pp. 1-3 (1955).

The Office played an even more critical role during the 1955-1976 copyright law revision effort in producing the current Copyright Act. As Bob Brauneis explains in his testimony, the legislative process

began with a series of 34 studies prepared by the Copyright Office over a five-year period addressing every corner of copyright law and of the economics of the copyright industries. Building on the insights of those studies, Register of Copyrights Abraham Kaminstein prepared in 1961 a comprehensive “Report of the Register of Copyrights on the General Revision of the U.S. Copyright Law.†Register Kaminstein then held a series of public meetings with copyright stakeholders to discuss the recommendations of that report, and gathered written comments as well. Having gathered that input, the Copyright Office then issued a “Preliminary Draft for Revised U.S. Copyright Law†in late 1962, and in 1963 held a series of public meetings discussing sections of that draft in detail. That led to the first bill introduced in Congress in 1964, which was used as the basis for another series of public meetings held by the Copyright Office. Finally, after a second bill was introduced in 1965, Congress itself began to hold hearings on the proposed legislation.

Since the Copyright Act of 1976, the Copyright Office has played a central role in copyright law and policy: advising Congress and the Executive Branch; providing guidance to courts, copyright practitioners, and the general public; and administering copyright registrations, recordations, and deposits. It has also taken on new substantive roles, such as recommending exceptions for the circumvention of technical measures under 17 USC § 1201. And copyright policy has increasingly been addressed at an international level in venues such as WIPO and the WTO, expanding the scope of the Copyright Office’s work.

A Look at the Copyright Office

In recent decades, there have been a number of looks at the structure of the Copyright Office and administration of the copyright system. (Although it’s worth noting that Benjamin Kaplan suggested a regulatory commission with power to “adapt the statute to changing realities” when “congressional responses are apt to be late or inadequate” in his 1967 work, An Unhurried View of Copyright.)

In 1986, the Congressional Office of Technical Assessment (OTA) released a report on “Intellectual Property in an Age of Electronics and Information,” which sought to examine “the impact of recent and anticipated advances in communication and information technologies on the intellectual property system.” Among the report’s recommendations were institutional changes, ranging from intermediate changes—increasing research, coordination, regulatory, or adjudicatory functions of existing agencies, for example—to the creation of a new intellectual property agency. A joint Congressional committee held a hearing on the report on April 16, 1986, but no further legislative action resulted.

On February 16, 1993, Rep. William Hughes introduced H.R.897, the Copyright Reform Act of 1993. Among other things, the proposed bill would have made the Register of Copyrights a Presidential Appointee. This would have allowed the Register to make rules rather than requiring rules to be adopted by the Library of Congress. The Librarian of Congress, James Billington (who still serves in that capacity), opposed this move. He said in Congressional testimony,

At a time when publishing and communication are experiencing technological breakthroughs, it is particularly critical that the interests of the Library, the Copyright Office, and their constituents, be treated as mutual and complementary. The Library must be able to work hand in hand with the Copyright Office to ensure the continued collection, preservation, and protection of published and unpublished materials, including the new electronic information media that are making an increasingly important contribution to the nation’s intellectual heritage. 6Statement of James Billington, Hearings on H.R. 897: Copyright Reform Act of 1993, pg. 191, before the House Judiciary Comm. Subcomm. on Intellectual Property and Judicial Administration, 103rd Congress (March 4, 1993).

Hughes encouraged Billington to study further the effects his bill would have on the Library’s functions, and in response, Billington created an Advisory Committee on Copyright Registration and Deposit (ACCORD) to analyze these issues. Although the 20 member Committee (which included current Register of Copyrights Maria Pallante, then serving as Executive Director of the National Writers Union) did not examine the institutional changes contained within the Copyright Reform Act, it did look at registration and deposit issues.

The report of the ACCORD co-chairs presciently observed

As the communications revolution gathers momentum and the information superhighway is in its early stages, a comprehensive and reliable copyright database, available freely to the general public, is an enormous asset for a number of purposes. These matters were addressed during the ACCORD deliberations and by the individual authors of the working papers prepared for ACCORD discussions. There was consensus among ACCORD members that information obtained through registration-information bearing on authorship/dates of creation and publication, the ownership and duration of copyright, and the like can be extremely valuable not only for business transactions such as transferring rights, and obtaining permissions or licenses, but also for resolving legal disputes, providing biographical information, and so forth.

The Senate subsequently held a hearing on its companion bill, but while the legislation passed the House, it did not go any further. The issues raised by the report, however, did not disappear.

In 1996, Senator Orrin Hatch introduced an omnibus patent act which would have established a single government corporation to formulate policy and administer all forms of intellectual property: patent, trademark, and copyright. During a hearing on the bill, Hatch explained the motivation behind the change. First, he said, “The locus of copyright policymaking has shifted to the executive branch primarily because the international dimension of copyright has become dominant,” so the Copyright Office needs to be in the executive branch if it is to continue to play a leading role in policymaking. Second, Hatch noted the potential for increased rulemaking authority for the Copyright Office in the digital age—”For example, it has been suggested that the Copyright Office might administer a system of virtual magistrates for fair use and Internet access provider liability.” Increased executive powers, said Hatch, would cause problems given the Office’s current “anomalous position in the legislative branch.” Finally, Hatch said, the shift would “free the Copyright Office from the lengthy and cumbersome hiring practices of the Library of Congress.”

Register of Copyrights Marybeth Peters sharply criticized the proposal during her testimony, calling it “hasty and radical” and spoke on a number of issues such a change would raise. The move “first and foremost” would require a “fivefold increase” in registration fees, leading, consequently, to a decrease in registrations and Library of Congress deposits. Second, the move has “the potential to politicize copyright policy.” Under the Library of Congress, said Peters, the Copyright Office is not “influenced by political agendas or subject to interagency clearance.” Third, the combination of copyright with patent and trademark raises “conceptual concerns” because of fundamental differences between the two. Copyright has strong cultural, educational, and expressive policies not present in patent and trademark, and “These values may be slighted if copyright policy is wholly determined by an entity dedicated to the furtherance of commerce.”

Peters concluded by raising questions concerning the need for change and potential consequences, and said

Answering all of these questions requires consultation with the affected communities to determine their needs and to weigh their perspectives. That process has not taken place. There has been no open, public debate of the issues involved. Neither the Copyright Office nor members of the private sector participated in formulating these proposals. No representative of the author, copyright owner, or copyright user communities were given the opportunity to testify today and no further hearings are scheduled.

William Patry testified in support of the bill on a following panel, calling the current placement of the Copyright Office in the legislative branch a “historic anomaly” and arguing that if the agency is to engage in executive functions, it should reside in the executive branch. But overwhelmingly the sentiment from participants in the hearing was against the move. Statements from other copyright groups almost universally agreed with Peters’ assessment. The bill did not make it out of committee nor reemerge during later Congressional sessions.

A New Great Copyright Agency?

The challenges facing the Copyright Office only continue to grow as technology advances and copyright policy becomes more central to society. As I noted in 2015 in Copyright Law and Policy, Register Pallante has said “Evolving the Copyright Office should be a major goal of the next great copyright act.” She elaborated on the staffing, funding, and technological challenges of the Office in a 2013 lecture and a 2014 House IP Subcommittee oversight hearing.

The House Judiciary Committee hearing today will focus not only on those challenges but also look at potential solutions. These include increasing the Copyright Office’s administrative authority, shifting it to the Department of Commerce, or creating a freestanding, independent agency outside the Library of Congress. Though there is no clear consensus yet on which avenue to take, the witnesses are in remarkable agreement about the critical role the Office plays, the need to modernize it, and the deficiencies in the status quo. The benefits of modernizing the Office would be shared by authors, users, and the general public. That means that Congress is presented with a rare opportunity to take a bold step in improving the law that would not likely be divisive—something presently rare in the world of copyright.

References

| ↑1 | Federalist 43. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Act of July 8, 1870, §§85-111, 41st Cong., 2d Sess., 16 Stat. 198, 212-16. |

| ↑3 | John Y. Cole, Of Copyright, Men & a National Library, The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Vol. 28, April 1971. See also A Visit to the Library of Congress. |

| ↑4 | Act of February 19, 1897, 54th Cong., 2d Sess., 29 Stat. 545. |

| ↑5 | Abe Goldman, The History of USA Copyright Law Revision from 1901 to 1954, Copyright Law Revision Study No. 1, pp. 1-3 (1955). |

| ↑6 | Statement of James Billington, Hearings on H.R. 897: Copyright Reform Act of 1993, pg. 191, before the House Judiciary Comm. Subcomm. on Intellectual Property and Judicial Administration, 103rd Congress (March 4, 1993). |