This past weekend, my parents came to visit me in my new place in Washington, DC. They wanted the “grand tour” of the city, and, as I myself had yet to do the tourist thing, I asked around for recommendations beyond the obvious drive past monuments. At the top of the list: the Library of Congress, which had the added bonus of being open to the public on Presidents’ Day.

Located next to the U.S. Capitol building at the top of the Hill, the Library actually consists of three primary buildings: the original building (renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building in 1980), the John Adams Building, and the James Madison Building. The Library itself was established in 1800 and was initially, well, a library for the use of Congress. Most of the library’s collection was burned by the British in 1814, but was replenished after Thomas Jefferson offered to sell the Library books from his own extensive collection. Beginning in the 1850s, there was a push to create a National Library in the U.S., and the Library of Congress grew (unofficially) into that role under the leadership of Ainsworth Spofford, who directed the Library — and pushed its expansion — from 1865 until 1897. Today, the Library is the largest in the world, with over 150 million items in its collection, including over 20 million books. It’s also worth noting (since this is a copyright blog) that since 1897, the Library of Congress has housed the U.S. Copyright Office.

The Great Hall and exhibition areas of the Thomas Jefferson Building are open to the public Monday through Saturday, with guided tours led by Library of Congress docents several times throughout the day. I’d highly recommend a visit and a tour, as this is one of the most remarkable buildings ever built. If you would build a cathedral for science and useful arts, it would look like this. Every inch of the walls and ceilings are covered with murals and sculptures, created by over 40 individual artists. Amazingly, this artwork was possible because as the building was being constructed, it was under-budget — not something typically associated with government work. And even with the additional cost of commissioning artwork, the final cost of the Thomas Jefferson Building was less than planned. For a complete description of all the works one can see in the building, see the Library’s On These Walls pages.

The Great Hall and exhibition areas of the Thomas Jefferson Building are open to the public Monday through Saturday, with guided tours led by Library of Congress docents several times throughout the day. I’d highly recommend a visit and a tour, as this is one of the most remarkable buildings ever built. If you would build a cathedral for science and useful arts, it would look like this. Every inch of the walls and ceilings are covered with murals and sculptures, created by over 40 individual artists. Amazingly, this artwork was possible because as the building was being constructed, it was under-budget — not something typically associated with government work. And even with the additional cost of commissioning artwork, the final cost of the Thomas Jefferson Building was less than planned. For a complete description of all the works one can see in the building, see the Library’s On These Walls pages.

For example, in the East Mosaic Corridor, murals on the wall and ceilings depict 13 fields of knowledge — including, as shown in the photo, law — as well as native-born Americans celebrated in those fields (for law, these Americans are Shaw, Taney, Marshall, Story, Gibson, Pinckney, Kent, Hamilton, Webster, and Curtis).

For example, in the East Mosaic Corridor, murals on the wall and ceilings depict 13 fields of knowledge — including, as shown in the photo, law — as well as native-born Americans celebrated in those fields (for law, these Americans are Shaw, Taney, Marshall, Story, Gibson, Pinckney, Kent, Hamilton, Webster, and Curtis).

Monday was also one of only two days each year that the Main Reading Room is open to the general public — and photography is permitted.

The Main Reading Room

Featured in the 2008 film National Treasure: Book of Secrets (a major driver of awareness about the room, judging by comments I overheard), the magnitude of the Main Reading Room is difficult to convey in photos — though the Library of Congress does offer a virtual tour if you can’t make it in person. Capped by a dome 125 feet in the air, surrounded by marble Corinthian columns (decorated with American tobacco leaves instead of the traditional acanthus) and 11-foot bronze statues, the Main Reading Room does a good job of inspiring awe.

Featured in the 2008 film National Treasure: Book of Secrets (a major driver of awareness about the room, judging by comments I overheard), the magnitude of the Main Reading Room is difficult to convey in photos — though the Library of Congress does offer a virtual tour if you can’t make it in person. Capped by a dome 125 feet in the air, surrounded by marble Corinthian columns (decorated with American tobacco leaves instead of the traditional acanthus) and 11-foot bronze statues, the Main Reading Room does a good job of inspiring awe.

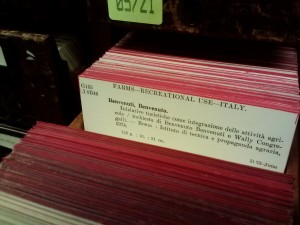

Also open to the public and adjacent to the Main Reading Room is the Main Card Catalog, which houses part of the Library’s old card catalog. No, the Library does not still maintain this. The Library had long ago moved to a computerized catalog — no new cards have been added since 1980, but it has kept the old system around.

Also open to the public and adjacent to the Main Reading Room is the Main Card Catalog, which houses part of the Library’s old card catalog. No, the Library does not still maintain this. The Library had long ago moved to a computerized catalog — no new cards have been added since 1980, but it has kept the old system around.

To the left is an example of an individual card.   The Library’s catalog is available online, with a newer version at catalog2.loc.gov that also includes links to resources where you can search other collections and archives beyond books. Here, by the way, is the digital version of the card in the photo.

The Library’s catalog is available online, with a newer version at catalog2.loc.gov that also includes links to resources where you can search other collections and archives beyond books. Here, by the way, is the digital version of the card in the photo.

The Library is a monument to knowledge, the artwork in the Thomas Jefferson Building practically consecrates the book. And since this is a site dedicated to copyright, I’d like to point out the pivotal role copyright law has played in creating the world’s largest library.

Copyright Deposit

Two provisions in the Copyright Act have provided the Library of Congress with many of the materials in its collection.

First, the US Copyright Act allows for voluntary registration of copyrighted works with the Copyright Office. Registration is not a prerequisite for protection, but it does confer a number of benefits, including the ability to file a civil suit for infringement and the ability to seek certain remedies, such as statutory damages. 1See 17 U.S.C. § 408(a), 411, 412. Registration requires the submission of two copies of the work; 217 U.S.C. § 408(b). this serves to provide a record of exactly what work a specific registration covers. The Copyright Office forwards one copy of works acquired here to the Library of Congress to use in its collection.

Separately, under 17 U.S.C. § 407, the owner of a copyright is required to deposit two copies of a work with the Library of Congress within three months of publication. While deposit is not a prerequisite for copyright protection (that is, if you fail to deposit, you do not lose your copyright), the Register of Copyrights may demand compliance from any copyright owner who fails to deposit, and the law provides for fines for non-compliance. And, perhaps a bit surprisingly, the Copyright Office does exercise this authority; in 2010, it made over 4,000 demands for certain titles. 3U.S. Copyright Office, Fiscal 2010 Annual Report, pg. 32.

In 2011, over 700,000 works were added to the Library of Congress under the first provision, over 300,000 under the second. 4Library of Congress Annual Report 2011. It would have cost the Library over $30 million to acquire these works if it had to purchase them.

Laws of the latter kind — which might be called “legal deposit” laws and are distinct from any copyright system — first appeared in Western Europe during the Renaissance. 5Elizabeth K. Dunne, Deposit of Copyrighted Works, Copyright Law Revision Study 20, pg. 1 (US Copyright Office, 1960). The earliest is from France — the Ordonnance de Montpellier, 1537. Similar laws spread throughout Europe, and England enacted a legal deposit system in 1662.

In the US, the 1790 Copyright Act provided for deposit only for copyright registration purposes, which was handled by the District Court nearest an author. A copy of each book registered was to be sent to the Secretary of State. The first attempt at legal deposit was made when the Smithsonian Institute was created in 1846, which provided that copies of each book registered under the copyright law be sent to both the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress. Few authors and publishers complied with this provision, however, and the requirement was repealed in 1859.

When Spofford took charge of the Library of Congress, he set his sights on legal deposit rules that would actually work. After a few unsuccessful attempts, Congress achieved that goal in its 1870 general revision of the copyright laws. The effect was immediate and substantial. In a 1960 study on legal deposit, the U.S. Copyright Office noted, “By 1875, copyright had become the Library’s largest source of acquisition for books and almost the only source for some other materials.” 6Id. at 14.

The great value of the copyright deposit to the collections of the Library of Congress since 1870 has been recognized many times. In the past it has materially assisted the Library in building its collections on all aspects of American history, literature, law, music, and social culture. 7Id. at 30.

References

| ↑1 | See 17 U.S.C. § 408(a), 411, 412. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 17 U.S.C. § 408(b). |

| ↑3 | U.S. Copyright Office, Fiscal 2010 Annual Report, pg. 32. |

| ↑4 | Library of Congress Annual Report 2011. |

| ↑5 | Elizabeth K. Dunne, Deposit of Copyrighted Works, Copyright Law Revision Study 20, pg. 1 (US Copyright Office, 1960). |

| ↑6 | Id. at 14. |

| ↑7 | Id. at 30. |

Thanks for the LOC tour. It is an impressive place. You might want to also visit the Copright Office across the street. Not as impressive, for sure, but they do have some interesting exhibits, like the Maltese Falcon statue from the Bogart movie in the Warner Bros. v. CBS case. If they know who you are and that you are coming they might even arrange for a bit more of a tour behind the scenes. They did that for me as an educator.